First the confession: I’d picked Going to the Dogs: The Story of a Moralist by Erich Kästner as part of my German Literature Reading Month participation. Well that was November and this is December, so forget the reading month. Or not. One of the books I read and thoroughly enjoyed for German Lit Month was Heinrich Mann’s Man of Straw. It’s currently OOP in English and seems sadly neglected, yet after concluding the novel, I cannot but think that this is a seminal novel for its depiction of the militaristic features of Wilhelmine Germany. And that brings me to Going to the Dogs. We’re back in Germany, but it’s a terrible state of affairs. All that discipline and saber-rattling from Man of Straw appears to have disappeared and instead we are presented with the ultra-decadence of Weimar Berlin.

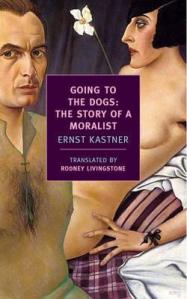

Originally titled Fabian (after the main character), the book appeared in 1931. My copy is from New York Review Books, and it’s not a new translation. It’s the original translation by Cyrus Brooks, but this edition includes an Epilogue (“rejected by the original publisher“) and the Preface (added by Kästner for a later edition). There is also an extensive and informative introduction which addresses various interpretations and criticisms at the front of the book by Rodney Livingstone, and for those who don’t want to know how the book ends, I recommend reading the intro after you’ve read the book. Going to the Dogs is considered one of the key novels from Weimar Berlin, so add it to your reading list if you want to dig around in this period. In spite of the fact that the action takes place in the giddiness of a very decadent society, this is not what I would call a fun or light-hearted read, and that’s due in part to the main character, Fabian who’s often revolted by the society in which he struggles to survive. But there’s a second reason why this novel is a somewhat depressing read, and that’s because we know that Weimar Berlin, in all its frantic, frenetic, tawdry glory is spinning out of control; it’s on it’s last legs and its about to swept away and replaced by Hitler and the Nazis.

Originally titled Fabian (after the main character), the book appeared in 1931. My copy is from New York Review Books, and it’s not a new translation. It’s the original translation by Cyrus Brooks, but this edition includes an Epilogue (“rejected by the original publisher“) and the Preface (added by Kästner for a later edition). There is also an extensive and informative introduction which addresses various interpretations and criticisms at the front of the book by Rodney Livingstone, and for those who don’t want to know how the book ends, I recommend reading the intro after you’ve read the book. Going to the Dogs is considered one of the key novels from Weimar Berlin, so add it to your reading list if you want to dig around in this period. In spite of the fact that the action takes place in the giddiness of a very decadent society, this is not what I would call a fun or light-hearted read, and that’s due in part to the main character, Fabian who’s often revolted by the society in which he struggles to survive. But there’s a second reason why this novel is a somewhat depressing read, and that’s because we know that Weimar Berlin, in all its frantic, frenetic, tawdry glory is spinning out of control; it’s on it’s last legs and its about to swept away and replaced by Hitler and the Nazis.

The book is set in Berlin in the late 1920s. The intro explains that there were 350,000 unemployed in 1930 Berlin but that zoomed to 650,000 just two years later, and that “one Berliner in four depended on welfare payments.” On to “the elections of September 1930 [when] five and a half million people voted for the NSDAP … making it the second largest party in Prussia.” The tone in Germany was shifting and the “pre-dominant atmosphere was right-wing.” Swastikas are mentioned in the book, and it is clear that society is in a state of chaos, a freefall, and of course, we all know where society landed when Hitler became Chancellor in 1933.

Kästner, who was born in 1899 and died in 1974, managed to live in Nazi Germany in spite of the fact that his books were banned and burned–with the exception of his 1928 novel, Emil and the Detectives. The others were personally consigned to the flames by Goebbels on May 10, 1933. As the introduction explains, there’s a great deal of Kästner in the character of Fabian–although perhaps the creation of Fabian allowed Kästner to survive in an ever-changing Germany. When reading Going to the Dogs, it becomes clear that Fabian isn’t really part of society. He’s an observer–a wounded morally lost observer. The society in which Fabian flounders clearly profits the opportunistic. Count Fabian out on that score. But that said, Fabian doesn’t particularly condemn Weimar society, but neither does he participate. He watches….

The book begins with 32-year-old Fabian earning 200 marks a month as an advertising copywriter. This is just the latest in a series of jobs, and with rent at 80 marks a month, it’s a marginal, unstable living. At the newspaper office, the political editor , Münzer, arguing that “what we make up is not half as bad as what we leave out,” believes in fabricating stories to fill up space, and when he invents a story about street fighting in Calcutta with “fourteen dead,” he tells his officemates to “kindly prove” him wrong:

There’s always fighting in Calcutta. Are we to report that a sea-serpent has been sighted in the Pacific? Just remember this: reports that are never proved untrue –or at least for a week, or so–are true.

Not far into the novel, Fabian loses his job, and if things looked bad before, they quickly become hopeless. The streets are full of drifters, hungry unemployed men, prostitutes, and sex-crazed women, and a visit to the unemployment office underscores the destruction and uselessness of societal institutions.

In the midst of Fabian’s bleak despair, the novel contains some very funny scenes which emphasize the feeling that society has gone insane, and in one of the book’s best scenes, Fabian attends a cabaret in which the acts are performed by lunatics. As the acts, managed by a man called Caligula, become more outrageous, the audience grows increasingly out of control until a “lanky ballad-monger” begins catching, by mouth, the lumps of sugar thrown at the stage.

One of the arguments concerning the novel is whether Fabian is a critic of his society or whether he’s a product. I’d argue that he’s both. He attends orgies out of curiosity, turns down an offer to become a male prostitute, constantly fights off sexually rapacious women, and lives in a state of despair at the state of humankind:

If you are an optimist, you should despair. I am a melancholic, so nothing much can happen to me. I don’t tend towards suicide, for I feel nothing of that urge to action which makes others go on butting their heads against a wall till their heads give way. I look on and wait. I wait for the triumph of decency; when that comes, I can place myself at the world’s disposal. But I wait for it as an unbeliever waits for miracles.

But just as Fabian’s life appears to hit rock bottom, he meets a young woman who has ambitions to become an actress.

My conviction is that there are only two alternatives for humanity in its present state. Either mankind is dissatisfied with its lot, and then we bash each other over the head in order to improve things, or, and this is a purely hypothetical situation, we are content with ourselves and the universe, and then we commit suicide out of sheer boredom.

Going to the Dogs: The Story of a Moralist offers a contrast to Man of Straw. The sane, decent or kind people do not fare well in Fabian’s Berlin, and Fabian, who doesn’t think that anything will change as long as people are “swine” senses another war ahead. Here’s a clip from Fabian’s nightmare:

In front of them towered a machine as vast as Cologne Cathedral. Before it were standing workmen, stripped to the waist. They were armed with shovels, and were shoveling hundreds of thousands of babies into a huge furnace where a red fire was burning.

Uncanny when you think that this was published in 1931.

And now we are again seated in the waiting room, and again its name is Europe.

This piques my interest quite a bit – must add it to the ever-expanding TBR pile.

The paragraph about the two alternatives reminded me – although it’s not really apposite – of Camus’ The Myth of Sisyphus – in fact, the tone of your post generally made me think of Camus. Did you find any parallels, in terms of writing style or, more importantly, I suppose, world-view?

It’s been decades since I read Camus so I can’t comment on that. I didn’t make the connection when reading this, but if you did, you must be on to something.

I’ve got his collected works in a cellar somewhere. I’ve read quite a few of his novels and liked them all but never this one. I should do that, I’m sure I would like it. I didn’t know it was translated as in German it still has the title Fabian. The last quotes are quite chilling.

The intro in this is well worth catching (even if it contains the biggest possible spoiler) as it includes a lot of the criticism of the novel. Short stories by this author sound tantalizing.

yes that second to last quote about the fire and the babies being shoveled in. I had to reread that a couple of times. Chilling indeed.

This book is set in a very interesting time period. It sounds like Kastner intertwines his themes with history a bit here. Of course I love it when an author does such things.

I have an attraction to the time period partly for its decadence and partly because it’s as though people were caught in some giddy spin out before facing total destruction.

On my list, Guy…. Roll on 2013, when I might have more time to read….

Dare I hope that that means you may be close to completing the next novel.

Wow, this sure sounds fascinating. It makes me think of Maurice Sachs. Do you remember this book? The last quotes are incredible, this man had the lucidity to see where things were going. Or the intuition because I’m sure he wasn’t able to imagine the unimaginable.

The author seems to be rather an odd figure, Emma. In the intro, it mentions that Kästner arrived back in Berlin just as some of his friends were fleeing. Apparently he managed to live in Germany and was more or less left alone (was ordered to the Gestapo a couple of times). He stayed in Germany to take care of his mother and seems to have kept his head down, but at the same time, as you say, he appears to have sensed that something awful was about to happen.

I can see why it makes you think of Sachs as Kästner is one of those sideline characters too.

The link I make is with Isherwood, but possibly because I read Goodbye to Berlin last year. This sounds like it’s riper. Am interested, thanks for the tip Guy.

Yes there’s a connection but I think Kastner is more pessimistic IMO.I think you’d like this.

I had to read your review as I loved his one book that wasn’t consigned to the fire, Emil and the Detectives which was perhaps a lighter read than this one. It does sound interesting especially his the time period it is set in – one for a more serious moment I feel.

Very Weimar Berlin, this one.