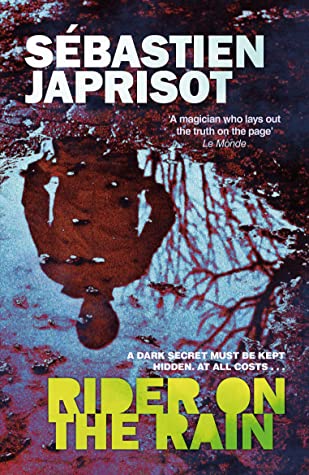

First: Rider on the Rain, the book was published in French in 1969 (per Goodreads), but Sèbastien Japrisot also wrote the screen play for the 1970 film which featured Charles Bronson with Jill Ireland in a supporting role. They met during filming while she was married to David McCallum. Bronson married Jill Ireland in 1968, and they were together until her death in 1990. The film showcases Bronson “at his brutal best,” and this period was the beginning of his film heyday, with the cult film, Death Wish still in his future in 1974.

So now onto the book: 25-year-old Mélancolie Mau, Mellie, lives in the dreary seaside resort town of Le Caps-des-pins. It’s the sort of place with one road in and one road out.

A peal of thunder, a grey river spattering in a downpour, a horizon blurred by autumn. And then the wheels of a bus send up great glistening sprays of water, and the river becomes a road running the length of a desolate peninsula, somewhere between Toulon and Saint-Tropez.

There’s the idea that not much happens here–at least it doesn’t until a stranger gets off the bus. Mellie sees the man, a man with a shaven head, carrying a bright red bag, get off the bus. Later, she tries on a dress in a shop owned by a friend. In the casual atmosphere, Mellie neglects to close the cubicle curtain and she catches the stranger staring at her through the shop window:

She is transfixed, as if mesmerized by his own fascination.

The stranger breaks into Mellie’s home and brutally rapes her. Mellie, who seems like a fragile young woman, calls the police but changes her mind. When she discovers the rapist in her basement, she strikes back. …. From this point, life changes for Mellie. She has discovered exactly what she is capable of, but in spite of this incredibly powerful knowledge, she chooses to sink back into her role as a wife, a rather docile wife to her macho dickhead of a husband. But then another man arrives on the scene, an American, Harry Dobbs. He’s looking for the stranger, and the bag he carried, and he knows that Mellie is hiding something. …

The dialogue is written in screenplay format, and the descriptive passages evoke images of the film. The novel is probably going to mean more to you (it did to me), if you’re a fan of the film. Harry’s relationship with Mellie, which becomes a sort of cat-and-mouse, is intriguing. It’s also fascinating that Mellie chooses to NOT tell her husband about the rape. On one level, this seems logical as her husband would go ballistic and probably start accusing her of somehow inviting the incident and ‘liking it.’ So ultimately it’s just easier not to tell him, but then also there’s the idea that Mellie keeps a certain section of herself submerged and secret. She has a “serene and well-groomed appearance” and yet “her nails are bitten to the quick.” There’s a level of protection, especially when dealing with a husband such as Tony, of withholding part of the self. He has no idea who she is–he’s constructed a version of her in his mind and then demands she conform to that. Yet Harry penetrates Mellie’s wall, her defenses. He intuitively knows that her outward fragility is a disguise, a bluff, a method of dealing with her surroundings. Ultimately: do we ever want people to know what we are capable of ?

Review copy. Translated by Linda Coverdale

You must be logged in to post a comment.