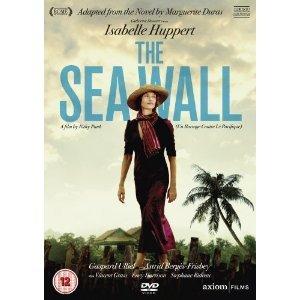

I recently watched the stunning film The Sea Wall (Un Barrage Contre Pacifique) starring Isabelle Huppert, and when I discovered that the film was based on a book, I decided to read it.

I recently watched the stunning film The Sea Wall (Un Barrage Contre Pacifique) starring Isabelle Huppert, and when I discovered that the film was based on a book, I decided to read it.

The Sea Wall is a semi-autobiographical novel written by Marguerite Duras. Years ago, I’d seen The Lover, based on yet another Duras novel, and although the film was a big hit, I wasn’t a fan, and I was certain I wouldn’t like her novels. But even with that prejudice in mind, I didn’t hesitate to buy the book version of The Sea Wall. I was hoping that the novel would add some of the details missing in the film. I was not disappointed.

The Sea Wall is the story of a middle-aged widow ‘Ma’ and her two children, twenty-year-old Joseph and sixteen-year-old Suzanne. Ma and her husband were French provincial schoolteachers who came to Indochina hoping that they’d change their fortunes:

The daughter of peasants, she had been so bright at school that her parents had allowed her to go to college. After that, she had been a schoolteacher for two years in a village in northern France. That was in 1899. Occasionally, on Sunday, she stopped to gaze at the Colonial propaganda posters in front of the town hall. “Enlist in the Colonial Army!” said some. And others: “Young People, a Fortune awaits you in the Colonies.” The picture usually showed a Colonial couple, dressed in white, sitting in rocking-chairs under banana trees while smiling natives busied themselves around them. She married a schoolmaster who was as sick of life in the northern village and as victimized as she was by the maunderings of Pierre Loti and his romantic descriptions of exotic lands. The consequence was that, shortly after their marriage, they made out a joint application to be sent, as teachers, to that great Colony then known as French Indo-China.

Basically they were sold a bill of goods. When the book begins, Suzanne & Joseph’s father is long dead and Ma, who remained in Indochina, has managed to support the children alone. First she earned a living giving French and piano lessons, and then for 10 years she played piano in a tiny “moving picture” theatre. Scraping up savings, she then applied “to the cadastral government of the Colony for a concession of land.” Ma, Joseph and Suzanne have lived on this piece of land for 6 years when the book begins, and life there is a disaster. The first year Ma puts half of the land under cultivation, but she bought land on a flood plain, so the land is flooded and the crop ruined. She tries the same the next year with the same results. The government agents who sold her the land were well aware that the land would flood, and of course there’s a little catch here. All the land must be under cultivation or it will be seized by government agents.

Ma finally “grasped the situation.” Up until that point she’d been “desperately ignorant of the blood-sucking proclivities of colonialism, in the tentacles of which she was hopelessly trapped.” The concessions are sold for twice their value with the agents taking half the amount of the sale. The agents have total control over land concessions. They say who gets what:

The concessions were never accorded except conditionally. If, after a designated period, the totality had not been put under cultivation, the Land Survey department would seize it. None of the concessions on the plain had been accorded a definite title; these were the concessions which easily enabled the land agents to make a considerable profit on the others, the real and arable concessions. The choice of attribution was left to them. The agents of the Land Survey reserved the right to distribute, according to their own best interests, immense reserves of irreclaimable land which, regularly attributed and no less regularly taken back, constituted in a way their reserve of capital. On the fifteen land concessions of the plain of Kam, they had settled, ruined, driven off, resettled and again ruined and driven off perhaps a hundred families. The only claim-holders who had remained on the plain lived by traffic in opium or absinthe, having to buy off the cadastral agents by paying them a quota of their regular earnings– “illegal earnings,” according to the agents.

When Ma complains that the land is worthless and that the agents knowingly sold land that she could not cultivate, the agents threaten to seize the land before the deadline for total cultivation is reached. This is, of course, the ultimate threat. Ma scrimped and saved to buy the land dreaming that she was creating a legacy for her children, but in reality, she’s only tied them to a place which holds no future for them. Both Joseph and Suzanne can’t wait to leave. Joseph has sidelines as a guide and as a smuggler, but Suzanne, however, has few options other than marriage to a stray hunter. There’s the sense of the uselessness of their continued existence. Joseph spends his nights hunting and slaughtering animals that the family find too repulsive to eat. Ma, Joseph and Suzanne spend their days “soaked in boredom and bitterness,” as they engage in an endless and futile battle against the elements and also against the impervious corruption of colonialism.

Not a great deal happens in The Sea Wall, and through this lack of action, the author creates a sense of ennui; Joseph and Suzanne are waiting for liberation, but that liberation will only arrive through the establishment of external relationships or through the death of their mother. Ma’s failing health seems to reflect the slow decay in which the family live. The large, but primitive house built on the property is mortgaged to the bank and the roof is rotting (as are Joseph’s neglected teeth). While the family seem to wait for something to happen there’s an underlying tension beneath all the inertia, depression and slow drift of day-to-day survival.

Not a great deal happens in The Sea Wall, and through this lack of action, the author creates a sense of ennui; Joseph and Suzanne are waiting for liberation, but that liberation will only arrive through the establishment of external relationships or through the death of their mother. Ma’s failing health seems to reflect the slow decay in which the family live. The large, but primitive house built on the property is mortgaged to the bank and the roof is rotting (as are Joseph’s neglected teeth). While the family seem to wait for something to happen there’s an underlying tension beneath all the inertia, depression and slow drift of day-to-day survival.

Something big does happen when Mister Jo, the son of a millionaire planter takes a fancy to Suzanne. Mister Jo becomes sexually obsessed with Suzanne, and she practices using her new-found sexual power, getting presents for her efforts. Suzanne’s relationship with Mister Jo is encouraged by Ma who in her turn becomes obsessed with the idea that Mister Jo’s wealth will solve all their problems.

The Sea Wall gives another view of colonialism, and the focus isn’t on the exploitation of the natives but the exploitation of those foolish and idealistic enough to cast themselves out into one far-flung outpost of empire. Ma and her children are cannibalized by the corrupt system, and consequently Ma is alienated from the country of her birth. She never talks of returning, and instead she hates colonial officials, identifies with the exploited natives, and encourages rebellion. This unforgettable novel includes many poignant details of local conditions–the massive die-off of local children and packs of starving dogs who trail after children in order to eat their excrement. This bleak, unshakeable image epitomizes the horrendous situation in Indochina and the pecking order of need. While The Sea Wall explores the corrosiveness of colonialism, on another level the story also explores parenthood and how the sacrifices parents make for their children are sometimes only an unwanted, heavy burden.

You must be logged in to post a comment.