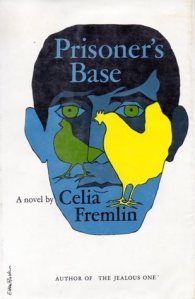

In Prisoner’s Base, author Celia Fremlin creates another hellish domestic environment which involves three generations. Grandmother Margaret owns a large home on land, and her married daughter, Claudia lives there too along with Margaret’s mostly absent son-in-law, and Claudia’s daughter, teenager, Helen. Claudia, known for her interest in strays (humans, not animals) brings a series of damaged people to stay in Margaret’s house. It is easy to describe Claudia’s interest in these strays as charitable, or even misguided, but Claudia’s fascination with damaged people is far more complicated. She loves to psycho-analyze, but there’s more to it than that; housing these strays inflates Margaret’s massive ego, sense of self-importance and righteousness. Margaret loves the vision of herself being generous, high-minded, and tolerant. But also these acts of charity, which appear to claim the moral high ground, seemed designed to feed hostility between Claudia and her mother, Margaret. There are frequent “Claudia-isms” “typical manoeuvre [s] to belittle and undermine” her mother whenever a point of dispute erupts. One Claudia-ism is to impute her mother’s opinions to the narrowmindedness of her generation. Another is to imply that any difference of opinion between mother and daughter is a sign of Margaret’s mental decline.

Claudia’s latest stray is the neurotic Mavis, who has been living with them for the past 5 months. Mavis, a little mouse of a woman who wanders around in her dressing gown has, according to Claudia, an “inferiority complex,” but with her self-effacing ways, she manages to ruin Margaret’s day by continually invading her privacy. Oh the delicate people of this world who must be handled like bone china.. . in case they break.

If she’d stolen ten shillings out of your handbag every day at one o’clock you could have had her put in prison, reflected Margaret sourly, and yet you had to stand by, helpless, while she stole one by one, far more than ten shillings worth of happy hours of solitude.

Claudia thinks Margaret should be grateful to have Mavis for company. So why doesn’t Margaret just tell Claudia that this is her house, that she won’t tolerate any more unwanted guests? The answer is that Claudia claims Margaret is small-minded and selfish and then again Claudia seems to be so good with these damaged souls which causes Margaret self-doubt. Margaret makes the error of questioning the validity of her own feelings and so she can never tell Claudia where to shove it. Claudia’s impositions are just part of an elaborate psychological game between Claudia and Margaret–Claudia with the moral superiority and Margaret painted, by her daughter, as selfish and dotty.

Claudia had always been an adept at putting you in the wrong before you had so much as opened your mouth; Margaret had been waiting for her to grow out of this unlovable talent ever since she was thirteen; but she never had. Indeed, she was getting better at it, and now, at nearly forty, she could switch off the family arguments before they began at all; like turning off the water at the main in some depressing outhouse to which she alone had access.

Problems in Margaret’s household erupt in two ways: First, Margaret discovers that Claudia is trying to sell the field (owned by Margaret) and is having it appraised:

“Now, don’t panic, Mother. Just relax. Why is it that women of your generation always have to be so tense? Naturally, the field has to be valued; and to be valued it has to be looked at. Doesn’t it? Surely that’s common sense? They have to send a man along. To look at it.” Claudia was emphasising the simplest of the one-syllable words as if she was hoping that these, at least, might come within the range of her mother’s intelligence.

Margaret is battling Claudia’s bullying attempts to sell when Claudia takes in a new stray. This one, Maurice, is an ex-con–possibly even a murderer, and Claudia is determined to bag this trophy after he pops up at the local poetry group. She brings him home to dear old mum. Even Mavis, who is Claudia’s sycophant, is disturbed by Maurice’s presence in the house. Convinced that Maurice is going to sneak into her room, it’s more than her nerves can handle. Claudia, ever a armchair voyeur, loves to hear about Maurice’s criminal exploits, but he’d rather she type up his 100s and 100s of dreary poems. The household becomes a simmering stewpot of resentments, fears and suppressed rage. So of course, something violent is going to occur. Prisoner’s Base is my favourite Fremlin novel so far. The dynamic between Claudia and Margaret is brilliantly drawn. For this reader, the relationship between mother and daughter was bitter and all-too real. On the surface, they coexist and are cordial, yet under the familial membrane are festering skirmishes. Fremlin creates a very a credible hell of everyday domestic nastiness, dominance and unhealthy relationships.

Interesting set-up I’m going to have to find out what happens. But are all the characters unsympathetic? Sounds like it.

I had sympathies for Margaret.

“another hellish domestic environment” Another? Seems like an odd thing to specialize in. But I can see how it would be useful for a writer of crime fiction.

Many people endure ongoing mental warfare at home. Fremlin captures that.